Many years ago I volunteered on a campaign for a friend running for a city hall alderman position (like a councillor, or whatever, you can figure it out).

Voting was done with paper ballots, and the way the votes were counted is very interesting, and has bearing with the recent news that foreign countries were able to hack in to American voting machines and actually change results.

The city had a ballot counter present at each precinct (voting hall). Each candidate was allowed to send in one representative to verify the count; that was my job. Scrutineers during the day had verified voter ID, so we could assume all the ballots were legitimate.

Each of us maintained our own count of the ballots. In our case, my total and the opponent's rep's totals were in agreement with the city worker's, so she simply phoned in the total into a central office. I don't remember what happened to the ballots, but I assume they were packaged and also sent to a city government office.

This system has so many good points.

1. It scales up, even nation-wide. If there are no challenges, ballots would be counted precinct-by-precinct, so counting up something like 300 ballots with, say, 30 questions (perplexing to Canadian readers, but not so unusual for the American readers, which is one of the reasons Americans have such low voting turnouts) would take maybe 6 hours (assume 9,000 separate votes each take two seconds to process, so that's about 5 hours, with another hour to do verification). The networks won't be happy that they can't release results at 8:10 PM Eastern time and call a winner at 11:15 PM once the west coast reports, but as we've seen, the price to pay for getting instant results is too high.

In a state-wide system, each precinct would report its totals to something like a county office, where the same n-way verification would take place. In this place each person would type in the totals and add them up in a spreadsheet. Yes, there's some copying and typing going on, with room for human error, but because there's an audit trail all along the way, discrepancies should be readily discovered and fixed. The counties then report their totals to a central state office. And anyone who watched the 2016 office knows that each of the networks is capable of adding up the sums for the electoral votes in each state.

So while I'm staying we shouldn't use computers to record the votes, there's nothing wrong with using them as a tool to help do simple math. In the absence of another Intel bug like the one 25 years ago that caused some spreadsheet-based errors, we're talking small integers here, the kinds almost any computer has no problem with, and spreadsheet templates can be prepared in advance.

2. It's not easily hackable. Maybe a ballot-checker could be a plant from an opposing party, but there's still a theoretically neutral government official counting the ballots.

3. It takes more time to fill in a ballot with a pen than using a computer. On the other hand, you can have many more people filling in cardboard ballots in parallel than having to wait for machines; you're only limited by the number of desks that you can put a privacy shield on and the number of pens to hand out. I expect this would be a win.

4. It involves more citizens in the democratic process, as we'll need a lot of people to help report the counts. This is a good thing.

5. There could be a public audit trail for the whole counting process, so anyone can see totals by precinct up to the district or state level, something we didn't have back in the paper-ballot days. You don't need a block chain, just a web site with PDF and CSV files. Ballot count verifiers should be given a card with the precinct count; if they see a different number on an official site it should be easy to launch an investigation. We couldn't have this back in the paper-ballot days because we didn't have web sites, let alone PDFs and CSVs, or even files.

This combines the best of electronic, paper, and human processes.

Or we can stick with using closed-source computers with undocumented but discoverable ports, and keep seeing people with questionable legitimacy step into positions of unearned power.

Thursday, July 26, 2018

Thursday, July 5, 2018

Autonomous cars and robots beating clothes on rocks

Here's yet another article on the problems with self-driving cars:

https://www.theverge.com/2018/7/3/17530232/self-driving-ai-winter-full-autonomy-waymo-tesla-uber

This article focuses on the problem of relying on using machine-learning to generalize from a corpus of real-world data to figure out how to build safe autonomous cars. Oh, I have an example. When I was teaching my 16-year-old daughter to drive, we were on a standard 4-lane road and I told her to slow down because we were approaching a shopping district. She asked why, when out of the blue she just passed a man in a mouth-propelled wheelchair going the wrong way between the parked cars and her car. And I seized the teachable moment to explain that slowing down gives you more time to anticipate the unexpected.

Machine-learning algorithms are crap when it comes to anticipating the unexpected. We humans excel at that, as slow as we are.

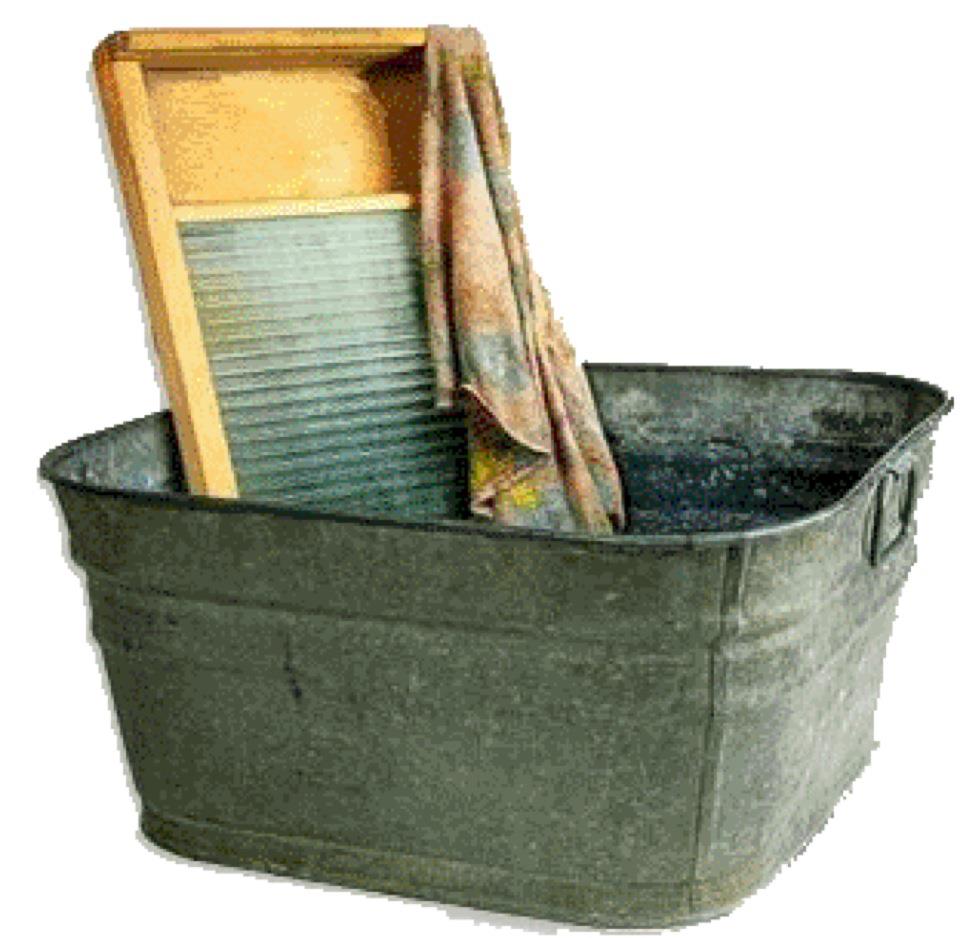

I was lucky to have studied computer science at the university that had hired David Parnas shortly after he resigned from Reagan's Star Wars panel. Word is that Parnas agreed to join the panel so he could publicly denounce it on his first day, claiming that since it would be impossible to test, it would be guaranteed to fail. That was the rumor. What I know for sure is that at one department colloquium he explained one problem with AI (at least as it was done in the late '80s) is that practitioners were focused on automating existing practices rather than looking to shift the paradigm. The example he gave is that if an AI researcher had designed the washing machine, we'd have a machine with a robot arm that would move clothes up and down a washboard.

Self-driving cars remind me of that washboard robot. People act like the problem they solve is that drivers are fallible, and would rather spend their time watching videos or working on their devices than pay attention to the road. One solution to that problem is to have robots drive the car, but it's not a good one. We've already seen that these robots will kill people in ways that no awake, sober human will (and those other humans aren't legally allowed to drive, so let's ignore them).

If you rise up one level, you see that this is just a system-level problem: how can we move people in large around a city, safely and cheaply? And if you go to most cities in northern Europe or Japan, you can see that problem was solved long ago, through ubiquitous, efficient public transportation combined with bicycle routes in some of those cities. Sure, those cities were designed around streetcars and peddlers pushing carts, not free-ranging cars. So North American cities, especially the ones that were built in the 50s and 60s assuming $2500 cars and 25 cent gallons of gas, need some adjusting, but it's happened in core Vancouver, and other cities are jumping on that bandwagon. And improving transportation and bicycle networks should be much cheaper than getting self-driving cars out of the lab and into widespread use.

So think of the self-driving car as the one-armed washing machine: it's a start, but we can do much better.

https://www.theverge.com/2018/7/3/17530232/self-driving-ai-winter-full-autonomy-waymo-tesla-uber

This article focuses on the problem of relying on using machine-learning to generalize from a corpus of real-world data to figure out how to build safe autonomous cars. Oh, I have an example. When I was teaching my 16-year-old daughter to drive, we were on a standard 4-lane road and I told her to slow down because we were approaching a shopping district. She asked why, when out of the blue she just passed a man in a mouth-propelled wheelchair going the wrong way between the parked cars and her car. And I seized the teachable moment to explain that slowing down gives you more time to anticipate the unexpected.

Machine-learning algorithms are crap when it comes to anticipating the unexpected. We humans excel at that, as slow as we are.

I was lucky to have studied computer science at the university that had hired David Parnas shortly after he resigned from Reagan's Star Wars panel. Word is that Parnas agreed to join the panel so he could publicly denounce it on his first day, claiming that since it would be impossible to test, it would be guaranteed to fail. That was the rumor. What I know for sure is that at one department colloquium he explained one problem with AI (at least as it was done in the late '80s) is that practitioners were focused on automating existing practices rather than looking to shift the paradigm. The example he gave is that if an AI researcher had designed the washing machine, we'd have a machine with a robot arm that would move clothes up and down a washboard.

Self-driving cars remind me of that washboard robot. People act like the problem they solve is that drivers are fallible, and would rather spend their time watching videos or working on their devices than pay attention to the road. One solution to that problem is to have robots drive the car, but it's not a good one. We've already seen that these robots will kill people in ways that no awake, sober human will (and those other humans aren't legally allowed to drive, so let's ignore them).

If you rise up one level, you see that this is just a system-level problem: how can we move people in large around a city, safely and cheaply? And if you go to most cities in northern Europe or Japan, you can see that problem was solved long ago, through ubiquitous, efficient public transportation combined with bicycle routes in some of those cities. Sure, those cities were designed around streetcars and peddlers pushing carts, not free-ranging cars. So North American cities, especially the ones that were built in the 50s and 60s assuming $2500 cars and 25 cent gallons of gas, need some adjusting, but it's happened in core Vancouver, and other cities are jumping on that bandwagon. And improving transportation and bicycle networks should be much cheaper than getting self-driving cars out of the lab and into widespread use.

So think of the self-driving car as the one-armed washing machine: it's a start, but we can do much better.

Monday, July 2, 2018

My Tabhunter Decade

See, I have a daughter who had taken up field hockey, and I happily ferried her and some team members to whichever field they were on that particular Saturday.

On weekdays I was working on a project where we were using Bugzilla to track everything -- bugs, features, chores: it was all in there. Bugzilla search was its usual taciturn self, saying "Zarro Boogs" regardless of what I put in the query box, so I adapted by simply never closing any tab that I had an interest in. I tried to group the tabs in particular windows based on some logical taxonomy, but too often when I was looking for something I'd end up listing all open bugs, and then searching by firefox search to find the bug I was looking for. I also tended to memorize issue numbers and would type them out in the address bar, to the amusement of one of my co-workers who is now a product manager on Firefox.

I wasn't really thinking about my tab management situation at that Coquitlam turf field, but at one point early in the game I watched one of the field-hockey fathers (a species not as well-known as soccer moms, but with better taste in beer), break away from our group and go mingle with the parents of the girls on the other team. How does this guy from Virginia know all these people from Coquitlam, I wondered? Oh right, he was the American consul to Vancouver at the time, and was doing what you'd expect a professional diplomat would be good at: mingle with pretty much anyone. And then I was struck by a bolt on how to deal with my tab problem:

I would write a Firefox extension, and I would have to call it "Tabhunter".

Firefox extensions had been around for a few years, and I had been working on a product that was built on Mozilla, so I was familiar with the tech. Greasemonkey had been around for 4 years, launched in late 2004. AdBlock Plus was about 2 years old. O'Reilly's "Firefox Hacks" came out in 2005. This wasn't exactly a new field, by industry standards. So that was my third bolt from the blue: it was about time I published my own extension as a side-project.

As for the name, I knew about the B-movie actor named Tab Hunter from the early 1960s because John Waters revived his career with three movies that came out some 25 years later: Polyester, Lust in the Dust, and the first Hairspray (the one with Divine, not John Travolta). I didn't know much about Tab, and back in those days there was no wikipedia to look things up, and I doubt there'd be much information on him in the Robarts library, U of Toronto's hulking brutualist peaon to book storage. But I knew he was a washed-up actor who Waters figured would be the perfect foil for Devine (an oversized cross-dressing actor (hard to use language when talking about him that isn't going to offend _someone_ -- hey, it was the '80s)).

|

| Robarts Library, the concrete goose named after the Ontario premier John, not the actor Jason |

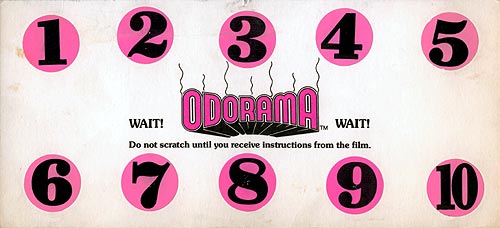

Polyester was brilliant, especially with its use of "Odorama". We were each handed a card with 12 brightly colored circles. When a number flashed on the screen, that was the signal to scratch the appropriate number and sniff your fingers. Like when the florist shows up at Divine's door with a bouquet of flowers. We won't know how the movie holds up without Odorama until the internet of smells is completed.

The name also was highly appropriate in a personal way. My last big side project involved applying the Kevin Bacon game to Amazon.com's "people who bought X also bought these 10 items". I called the site "The Amazing Baconizer", and killed it off when I was getting more traffic from hackers than users. But I was always looking with half-open eyes for another fun project with a pop culture name.

Developing the extension didn't take that long -- I had been working with the classic DOM API and Mozilla specifics for almost a decade, and knew enough CSS to make sure the extension didn't look horrible. In those days you had to get a review from a core member of the Mozilla project before it was accepted in the add-ons site. I recall my reviewer said the code was surprisingly good for a first timer. It could have been better, but it worked for me, helping me deal with 400 open tabs at a time instead of the previous limit of 200. Another extension, Bar Tab, kept most of my tabs unloaded. So I had access to the main details of each tab, but didn't have to have it loaded.

The field hockey season is short here - early April though early June, and I shipped in late June, so I can see I didn't procrastinate on this project.

The launch was fun. My favorite memory is the write-up in Gina Trapani's Lifehacker blog. Half the comments were from people who couldn't imagine having more than 6 or 8 tabs up at a time, and the other half were from people who couldn't believe an extension like mine shipped with every copy of Firefox. Plus a few shoutouts from people who also remembered Tab "space" Hunter, and thought the name was great.

Once the inevitable post-release bugs were fixed, I did almost nothing with the code until I had to perform a major rewrite to be compliant with Mozilla's new "Electrolysis" framework for Firefox, around 2014. The old framework was single-process, and my extension had direct access to everything it needed. The main part of Electrolysis was that the scripts of all the loaded web pages would run in one process, and the internal part, called chrome (the source of Google Chrome's name) would run in another process. The two processes would communicate via message-passing.

Tabhunter had always been open-source, but it was a typical open-source project in the way that apart from a couple of trivial pull-requests, I was doing all the work. This took a few weekends, and it wasn't a fun API to work with.

And then last year Mozilla announced that it was going to stop supporting all extensions based on current frameworks and APIs, and support only extensions using the new WebExtensions API, which would be more-or-less compatible with Chrome's API. This also meant rewriting the UI in standard HTML; previously the extensions were written in an XML-based UI-description language called XUL, which I was actually more comfortable with than basic HTML. You want to build a tree-widget in XUL, there's a

Once again I found a spare weekend to rewrite the add-on, and found the new WebExtensions API was straightforward to use, well documented, and performed really well. I also decided to try the browser-polyfill JS library and got Tabhunter running in Chrome, after all these years.

Also I discovered that someone had shipped a similar extension with a similar name (theirs has a space) to the Chrome store. It looks like a one-time thing -- it's still on version 0.0.1, only searches titles, and is missing all kinds of other useful features.

Since the current API is like an industry-standard, and feels more stable than anything before it, I started tackling all the feature requests and bug-reports that had built up over the years. My attitude had been that Tabhunter is an open-source project and I have always welcomed pull request submitters and even collaborators. But I knew many of my users weren't developers and would have no ability to scratch their own itches.

And almost everything went easily. Some of my favorite new features are highlighting duplicate tags (so if you see an orange line, you can delete it, as the first one will be in black text); selecting only the tabs that are blaring audio; and, on Firefox only, sorting tabs by what I call Neglect, which is the duration since a tab was last viewed. On my home machine I saw I had a few tabs that were 14 months old, from when I went to a talk on writing your own bot. If I hadn't looked at those tabs since then I wasn't going to write a bot anytime soon. Goodbye, natural-language-processing tabs.

Also, I worked out a decent build system to make it as easy as possible to target both Firefox and Chrome. It's all driven from a Makefile, and the goal is that you should be able to download the source (from https://github.com/ericpromislow/tabhunter/), run make, and end up with two zipfiles, one for each browser. About half the source files are .erb files, written in Ruby's preprocessor, and that lets me disable features in Chrome, like the aforementioned Neglect feature. Along those lines, there's no need to load browser-polyfill.min.js into the Firefox build, so it's loaded conditionally for the Chrome builds only. Yes, the only use of Ruby is in the build system. I could have used EJs, but I'm not a purist, and welcomed this surreptitious introduction of Ruby into the build system. I can run make after development, go to the Mozilla dashboard and load the firefox extension from the same directory, and then go do the Chrome dashboard and load a new version of a Chrome-compatible extension from the same directory as the previous version. I can upload both versions within 5 minutes after testing a new release.

As for Tabhunter's namesake, I hoped to get a testimonial from Tab Hunter himself for the launch. I found an 'info@tabhunter.com' address and wrote to it, but never heard anything. He's still around, and was even the subject of a 2015 documentary called "Tab Hunter Confidential". I proposed a meetup of the Vancouver Tabhunter Users Group in the lobby before or after the show, but was out of town the day it showed in town, and never heard if anyone attended. That's how we tab horders are -- quietly trying to deal with our internal demons, and closing tabs whenever we can.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)